The recent death of pioneer women's historian Gerda Lerner brought sadness and evoked a flood of personal memories.

Gerda Lerner taught at my alma mater, the University of Wisconsin at Madison (UW). She was hired a few years after I left. She helped create its first graduate program in women's history, as she had done when she taught at Sarah Lawrence College.

The memories are of that time, a turbulent time, when the experiences and voices and views of women were just beginning to be heard and taken seriously in the public arena. For me it was a time of change and reflection, a young mother, a historian and social activist, trying to find my place in the world.

Gerda Lerner taught at my alma mater, the University of Wisconsin at Madison (UW). She was hired a few years after I left. She helped create its first graduate program in women's history, as she had done when she taught at Sarah Lawrence College.

The memories are of that time, a turbulent time, when the experiences and voices and views of women were just beginning to be heard and taken seriously in the public arena. For me it was a time of change and reflection, a young mother, a historian and social activist, trying to find my place in the world.

The phone rang at our home on Robinwood Avenue in Toledo's Old West End. My girls, 7 and 10 years old, were out playing, their father teaching a class at the University of Toledo. It was the chairman of the History

Department, calling

I had just received my PhD in

American History at UW, in May 1975.

It had taken me some 10 years after completing my Master's thesis.

My girls were born inMadison, their doctor, Madeline Thornton, herself a pioneer, a rare woman doctor. We left Madison in 1968, a memorable year on every level. A whirlwind time. My friend Alice recently called it a "hyperventilated" time, which resonated. I was “ABD,” all but the dissertation. It was hard to focus on it, raise my

daughters and become involved in local civil rights and anti-Vietnam war

activities. My older daughter Elissa

remembers going on a grape boycott march with me at the local grocery store,

Caesar Chavez being a big hero in the Ohio/Michigan area then. Michelle remembers my going in a million directions. My dissertation was on the back burner.

It had taken me some 10 years after completing my Master's thesis.

My girls were born in

“How’s the dissertation

going?” my dad would ask me from time to time, calling from Rochester, NY, careful not to tread too much on

what had became a sensitive issue for me.

But his patience and confidence were eventually rewarded. He was the first person I called after I got the PhD. He was thrilled when I told him it was done, that I had a pleasant dissertation meeting back in Madison, and he could call me Dr. Fran Curro Cary.

But his patience and confidence were eventually rewarded. He was the first person I called after I got the PhD. He was thrilled when I told him it was done, that I had a pleasant dissertation meeting back in Madison, and he could call me Dr. Fran Curro Cary.

That's when I got the call about

teaching women’s history.

“No, I don’t think so," I responded. "I know

nothing about it. They didn’t have women’s history at the University of Wisconsin.

For that matter, I thought to myself, there were no

women on the UW faculty, and few women in graduate history seminars either. I think there was me and one

other student, Robin from NYC, serious and sophisticated, in my political history seminar with David

Cronon. It was a male environment.

Nor was I welcomed there at

first. The chairman of the department at

the time, the great American colonial scholar Merrill Jensen, whose work I revered as a

history major at Wheaton College in Norton ,

Massachusetts

“Are you engaged?”

“What do you mean?”

“Are you engaged to be married. I suppose you will be one of these days, then

you’ll get pregnant and leave the program,” he said, very seriously. “It would be a waste of a very competitive

position.”

Huh? Really? What was this

all about? I didn’t understand. I was nonplussed. I wasn’t

even thinking about anything else but continuing to study in a field I

loved. I was hardly a “feminist,” or

conscious of gender at all. Innocent. Naive.

I had come from an all-women’s college, graduated Phi Beta Kappa, Magna Cum Laude. I just happened to be one of the few women in myWheaton

l was taken aback at the Jensen interview. I went in with such excitement, and came out feeling a bit diminished. I brushed it aside. I took graduate school as a logical next step in my education. I had gotten a scholarship toWisconsin

I had come from an all-women’s college, graduated Phi Beta Kappa, Magna Cum Laude. I just happened to be one of the few women in my

l was taken aback at the Jensen interview. I went in with such excitement, and came out feeling a bit diminished. I brushed it aside. I took graduate school as a logical next step in my education. I had gotten a scholarship to

I forged ahead. Loved being a graduate student. I did get married. I did get pregnant. I did have to fight to get teaching assistantships, to be taken seriously. But I learned a lot, learned

a different way of looking at the world from the one I had inhabited in Rochester and at Wheaton

I remember having a long discussion on American foreign policy with a William Appleman Williams student who took me to interpretations I had never considered. I remember arguing about a recent study of slavery, Stanley Elkins I think it was, with a fellow graduate student at the base of the Abraham Lincoln statue on Bascom Hill; it was -30 degrees, beyond freezing, but that didn't stop us. I did get some frostbite on exposed knees, but so what?

I completed my MA thesis on journalist Walter Lippman and his view of the World Wars (which the department selected for publication, the only thesis selected at the time), and then continued my studies and research toward the PhD degree. When I came home from the hospital after delivering Elissa, I had 80 bluebooks on my desk, waiting to be graded. That was February 1965.

I remember having a long discussion on American foreign policy with a William Appleman Williams student who took me to interpretations I had never considered. I remember arguing about a recent study of slavery, Stanley Elkins I think it was, with a fellow graduate student at the base of the Abraham Lincoln statue on Bascom Hill; it was -30 degrees, beyond freezing, but that didn't stop us. I did get some frostbite on exposed knees, but so what?

I completed my MA thesis on journalist Walter Lippman and his view of the World Wars (which the department selected for publication, the only thesis selected at the time), and then continued my studies and research toward the PhD degree. When I came home from the hospital after delivering Elissa, I had 80 bluebooks on my desk, waiting to be graded. That was February 1965.

Three years later we were in Toledo, with Elissa and her baby sister Michelle, and all our belongings, mostly books, which we had packed into a flower-decorated VW bus. Toledo

You can teach Women’s

history, my husband prodded. Others

prodded, too. There was a demand for the

course. Students were hungry for new knowledge.

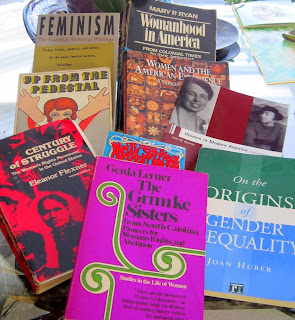

And so I said yes. I began my work teaching women's history in 1975, and continued teaching part-time until 1985. I created the course from scratch. I used every

book available (went back to Mary Beard and early writers on up) and whatever articles were being written and published, hot off

the presses. The new women's studies journals were a great help. Gerda Lerner’s Black Women

in White America was a bible, and so was Eleanor Flexner’s Century of

Struggle. I still think Flexner should be required reading for all college freshman. My students thought so too, so moved were they in reading it. I assigned Aileen Kraditor's Up from the Pedestal because it was a book of documents, where women's voices were heard directly, unfiltered through any intermediaries. These were such pioneering works. They gave meaning to women’s

experiences, perspectives and points of view. We learned about Abigail Adams, Prudence Crandell, Lucy Stone,

Elizabeth Blackwell, Maria Mitchell, the Grimke sisters, Angelina and Sarah, Sojourner Truth, Harriet Tubman, Elizabeth

Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, Carrie Catt, Alice Paul, Elizabeth Gurley

Flynn, Mary McCloud Bethune, and Margaret Sanger.

A whole new world opened up, a world where women were an integral part of the American experience and contributed to social change and reform, to equality in education, politics, the workplace, the professions. These were achievements that women fought for inch by inch, against ingrained prejudice and social outrage, against being thought of as "mannish" and worse, during times when public opinion stood soundly against them.

A whole new world opened up, a world where women were an integral part of the American experience and contributed to social change and reform, to equality in education, politics, the workplace, the professions. These were achievements that women fought for inch by inch, against ingrained prejudice and social outrage, against being thought of as "mannish" and worse, during times when public opinion stood soundly against them.

Gerda

Lerner was in that tradition. She helped us understand that women’s history was American history; that

the voices of women meant something, contributed enormously to American life, made America

But one thing is certain. We will have a woman president one day. And that woman will stand on the shoulders of the ordinary and extraordinary women who came before her. She will stand on the shoulders of the brave pioneers who fought fearlessly to move America toward it's ideals. Gerda Lerner and the hundreds of women's history scholars who have accompanied and followed her have taught us that. Gerda Lerner embodied our struggles and our dreams.

But one thing is certain. We will have a woman president one day. And that woman will stand on the shoulders of the ordinary and extraordinary women who came before her. She will stand on the shoulders of the brave pioneers who fought fearlessly to move America toward it's ideals. Gerda Lerner and the hundreds of women's history scholars who have accompanied and followed her have taught us that. Gerda Lerner embodied our struggles and our dreams.

No comments:

Post a Comment